Directing a film can feel like an all-consuming job, a labor of love. But for some directors, that passion forces them to take on more and more responsibility for their work. Not only because I can’t let go of control, but because I enjoy the whole storytelling process.

Some people edit their own films, like Josh Safdie (“Marty Supreme”), Chloé Zhao (“Hamnet”) and Kelly Reichard (“Mastermind”). Earlier this year, Sean Baker (“Anora”) became the second director to win an Oscar in the editing category, following Alfonso Cuaron for “Gravity.” Some directors wear two hats on set, either as an actor like Bradley Cooper (Is This Sing On?) or as a cinematographer like Steven Soderbergh and Zack Snyder. The ones with the least overlap in the Venn diagram are probably the directors who wrote their own music, led by Charlie Chaplin, Clint Eastwood, and John Carpenter.

It’s the most natural move for a director to double as an editor, as it’s an important extension of the storytelling.

“Editing is where the meaning of the film is truly born, so you can’t physically separate yourself from the material,” says Kauser Ben Hania (The Voice of Hind Rajab).

Helmer Kauser Ben Hania was involved in the cutting of “The Voice of Hind Rajab”.

“Voice of Hind Rajab” (Courtesy of Venice Film Festival)

Still, becoming an editor often begins more naturally. “In film school, if you don’t edit your film, no one will edit it for you, and on your first film, you edit out of necessity,” Cuaron says.

Reichardt said in an email interview that he had barely enough money to film “Old Joy.” “I didn’t have the money to hire an editor, so I cut the film myself.”

Currently, Reichardt edits films of his own choosing and wants to be a part of new ideas evolving in the editing suite. “I don’t want to miss any part of the process,” she says. “Editing is a place of discovery. I’m still amazed at how a few frames can change the mood of a conversation or the tension of a scene in this direction or that direction. I don’t want to miss any of it.”

If Reichardt had an editor, she would be annoyed. “It’s really boring, just sitting on the couch and watching someone cut,” she says.

Although Ben Hania collaborates with other editors and trusts their ideas, especially in the early stages, “you need to experiment alone to try things out,” she says.

But while Reichardt and Cuaron often share their work with collaborators, they say they’ve learned to be ruthless with their own footage.

“I value footage not because it looks good, or because it was the hardest day of filming, or because it was the most expensive,” Reichardt says. “I cut out entire parts of movies with actors I love. When I’m in doubt about something, I try to live without it. If I don’t mind its absence, I leave out that part.”

Cuaron said that when assembling the first cut, he kept his director’s hat on while shaping the larger story. “Then you kick the manager out and they get merciless,” he says. “I don’t care how difficult it was to get that shot, or how beautiful the light was, or that it took two days to achieve it.”

Director Chloé Zhao co-edited “Hamnet.”

Featured features

Even directors who give their films to editors may not be able to say no. Carpenter said he sometimes has an “obsessive” need to edit certain scenes. “For ‘Big Trouble in Little China,’ we edited out the big fight in the alley because we just had to get it,” he recalls.

Carpenter is known as much for his own composers as born of necessity, as for his editing of Reichardt. “In the beginning, I didn’t have the money to buy a good composer, so my father taught me things like violin and piano. I was only moderately talented, but once I got a synthesizer, I could make sounds like an orchestra,” he says, adding that it was his father who taught him the 5/4 time signature he used to write the iconic “Halloween” theme after an initial screening deemed it not scary enough. He continued writing scores because, although directing was his first love, it’s “so hard, so much pressure, but it’s so much fun to write music.”

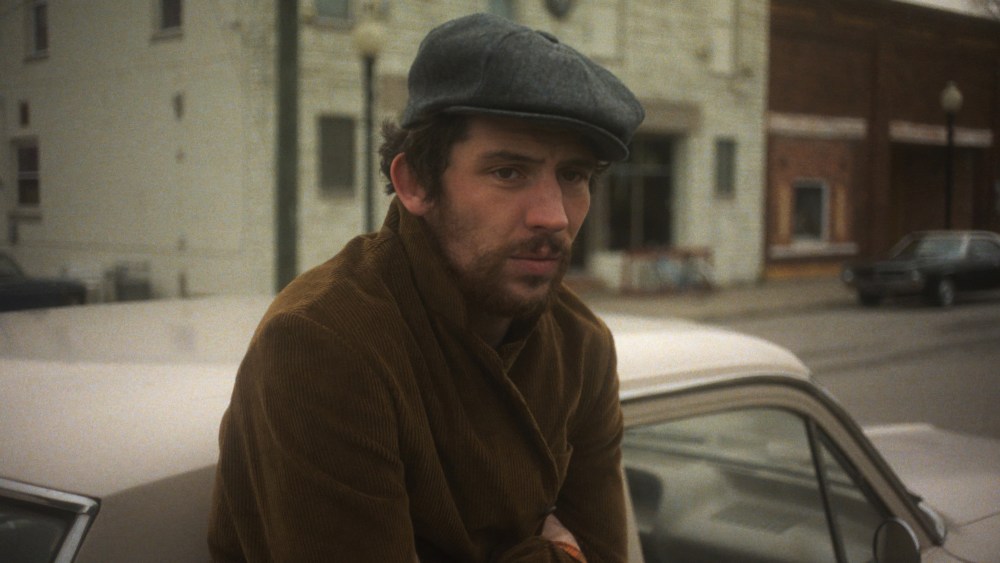

A bigger challenge for multihyphenate directors is juggling roles on set. Ben Jacobson co-wrote and co-starred with his best friend Moe Stark in his debut film, Bunny, but Jacobson always had to switch gears. He did so partly because they had written his character, Dino, as “a version of myself, a movie-obsessed, slightly hot-tempered personality,” and he couldn’t see anyone else in the role, and partly because he “wanted to dress up and play with my best friend.”

Still, once the cameras started rolling, he says, “I often wished I hadn’t acted,” so he could focus on directing. He had to rely on a third screenwriter, Stefan Malolachakis, to watch the monitor and evaluate the acting of each scene. Jacobson and Stark are preparing for their next film, with Jacobson set to play a smaller role. But if the producers said they liked the chemistry with Stark and wanted another buddy comedy, they’d consider it. “It depends on whether they give us money or not and pay for the movie,” Jacobson says with a laugh.

Snyder said that when he transitioned from a commercial job operating a camera to directing, he was told that being a cinematographer was difficult. “I said, ‘OK,’ because I didn’t know anything about the film industry,” he recalls. But on “Dawn of the Dead” and later “300,” he would often carry a B camera or run a small second unit while the cinematographer lit the large setup. “We wanted to shoot everything on time, so we just said, ‘Please let us go shoot to move us forward.'”

As his budget grew, such opportunities receded. “When you make a big movie like Justice League, the content becomes so extensive that it takes you away from the actual production,” he says. “That really frustrated me because I’m happiest when I have a camera in my hand.”

Although he always trusted his cinematographers and encouraged them to “flex their artistic muscles,” in the last five years he has made smaller films, starting with Army of the Dead, and asserted himself as a cinematographer. “It was the most liberating and happiest experience. This is why I make films,” he says.

Still, he admits it’s tiring. “We never stop,” he says. “From the moment you step on set to the moment you finally call rap, if you’re the director and the cinematographer, nothing happens without you. So you’re available 24/7.”

That may be why there are so few double directors, and why Cuaron is the only one to win an Oscar for cinematography. It was during ROMA, and it happened by chance. Cuaron was always shooting a few days of his own movies to keep things moving forward, and he did it for his friends as well. But in “Roma” he again turned to Emmanuel “Chibo” Lubezki. I co-produced five feature films with him. (Lubezki won an Oscar for “Gravity.”) But just weeks before filming began, Lubezki realized there was a scheduling conflict.

Director Cuaron asked him to recommend another cinematographer. “He said, ‘I have the perfect person, and it’s you.'” Daunted, Cuarón spoke with other directors he admired, but realized that “all the conversations would be in English, and I wanted to be fully immersed in my own language and memory for this film.”

Without Lubezki, there was a sense of tension on set. “The manager thought he was very slow, and the manager thought he was an asshole,” Cuaron said with a wry smile. However, he added that while he has no intention of working on two jobs at once again, “I loved it.I probably enjoyed “Roma” more as a director than as a director.”