It took Laura Poitras, the director of the Oscar-winning Citizenfour and the Oscar-nominated Woman in Blood, 20 years to convince Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Seymour Hersh to turn her career into a film. The long-gestating project finally became a reality three years ago, with Hirsch giving Poitras and his longtime friend and co-director Mark Obenhaus full access to his archives. The result of a monumental work of research and months of in-depth interviews is “Cover-Up,” which had its world premiere in Venice and is now showing at IDFA.

Speaking to Variety outside a festival in the Netherlands, the director duo said they spent three months creating a proof of concept for not just the film, but how they would work together, and planned their collaboration. Together with producer Olivia Streisand, the two conducted extensive preliminary research. “We really felt that we needed to know that we had a strong archival foundation that we could leverage,” Poitras says. “My approach to filmmaking is scene-based. I had questions like, ‘What footage from the ’60s and ’70s of Sy[Seymour’s nickname]talking about his work could I approach in a cinematic way?”

“From there, we generated ideas for how to interview him, which was a little unusual because there were three of us. Olivia also ended up participating in the interview, which gave us material that we could use to enhance our questions,” Obenhaus added. “The whole process was actually very original and unexpectedly unique to this project.”

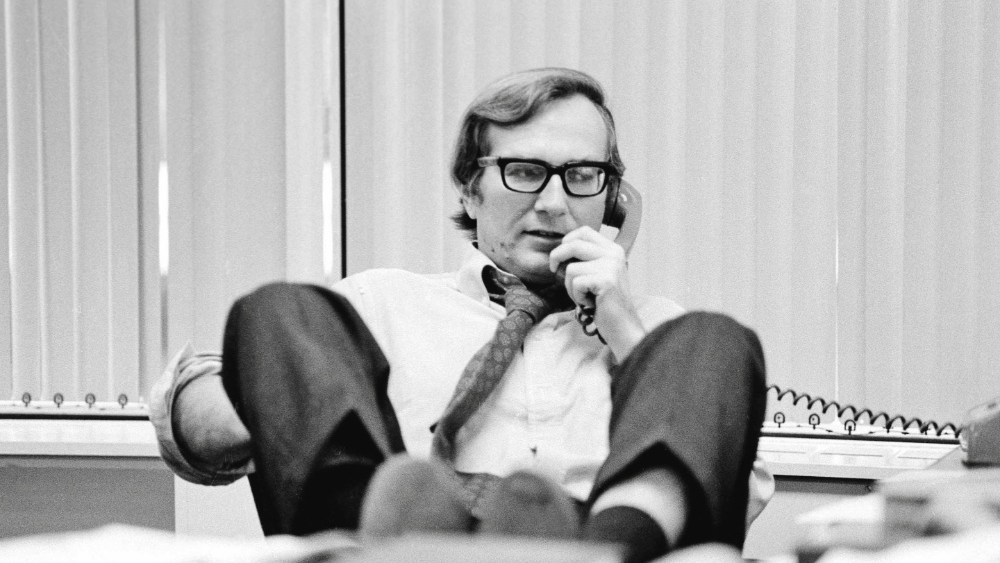

The film chronicles Hersh’s lauded career, from unraveling the My Lai massacre perpetrated by American soldiers in Vietnam, to writing dozens of novels about Watergate, to exposing major scandals such as the MK-ULTRA mind control experiments and the torture and abuse of prisoners of war by American soldiers at Abu Ghraib.

In his review of the film, Variety critic Owen Gleiberman questioned the current state of investigative reporting and why major news organizations like the New York Times don’t dig deeper into stories like the one about Jeffrey Epstein. “There were a lot of rules imposed on us because this movie is about America, not just Cy. This movie is not a biopic and we’re not interested in biopics. We were anchored by Cy and his reporting, but we always wanted it to be relevant to a modern audience,” Poitras said of the film’s relevance at a time when the increasingly volatile relationship between the U.S. government and traditional media is constantly making headlines, and the use of AI threatens audiences’ trust in news sources.

“Part of the fun of making this film was imagining how it would resonate with journalists, especially those working in traditional institutions,” Poitras said. “I can’t imagine a rhinoceros not being able to use certain words to describe what’s going on in the world. The idea that journalists shouldn’t be allowed to use words like genocide in today’s news organizations is a testament to what’s happening around us.”

Asked how he would view his film in light of President Trump’s threat to sue the BBC for libel over the editing of his Jan. 6, 2021, speech on the documentary Panorama, Poitras said that despite Trump’s history of threatening legal action against news organizations, in this case the British giant “made a mistake.”

“If you want to talk about the BBC, they made a mistake,” she stresses. “They should have retracted it. They should have immediately acknowledged it, corrected it, and apologized. They made edits that created a new meaning that didn’t exist. This doesn’t mean the institution has lost trust, but they made a mistake. When people talk about a lack of trust in the media, that’s what they mean. If you make a mistake, you have to admit it and be transparent with your readers, because otherwise you lose trust.”

Obenhaus added that although Poitras’ statement was “very true,” “the absolute irony is that if you go back one day through Mr. Trump’s list of factual distortions, all of us can find fault with this editorial issue. It’s breathtaking, and the irony of it all doesn’t escape me. Let me put it that way.”

Given the timeliness of the film, it becomes even more urgent for audiences to see it. Poitras partnered with Netflix for the first time on Cover Up, which released the film in select theaters in the UK and US on December 5th and then added it to its streaming platform in more than 190 countries starting December 26th.

“We are grateful for the support of Netflix and Plan B,” Obenhaus said. “However, I am concerned about the nature of streaming and how algorithms govern the suggestions given. Our hope is to expand the natural audience for this film to include viewers who may not know of See’s work or who think his experience as a journalist is relevant in today’s times. The jury is still out in my mind as to how successful it will be on Netflix, but I am very optimistic.”

Poitras stressed that it was “important” to note that Netflix “did not request any frame changes,” adding that the streamer’s reach was “extraordinary.” “I’ve never hidden the fact that I absolutely love and believe in theatrical screenings, especially that documentary, which is a movie and should have a life in theaters. We have three weeks. I wish it was longer, but I think a lot of filmmakers have said the same thing. I think everyone benefits from a longer theatrical run. I think movies can be part of the cultural zeitgeist. I fell in love with movies that are about sitting in a dark room with strangers, and I still believe that.

Regarding the decline in funding and institutional support for documentary makers, Poitras says attending festivals like IDFA allows people to see “the extraordinary work that filmmakers are doing” despite the challenges. “But we’re also seeing a reduction in funding and risk aversion in the distribution environment, especially for films with a political background. The documentary you’re watching is an extraordinary one, with unyielding risk-taking. There’s this bravery happening among filmmakers. What we’re seeing is the system failing us.”