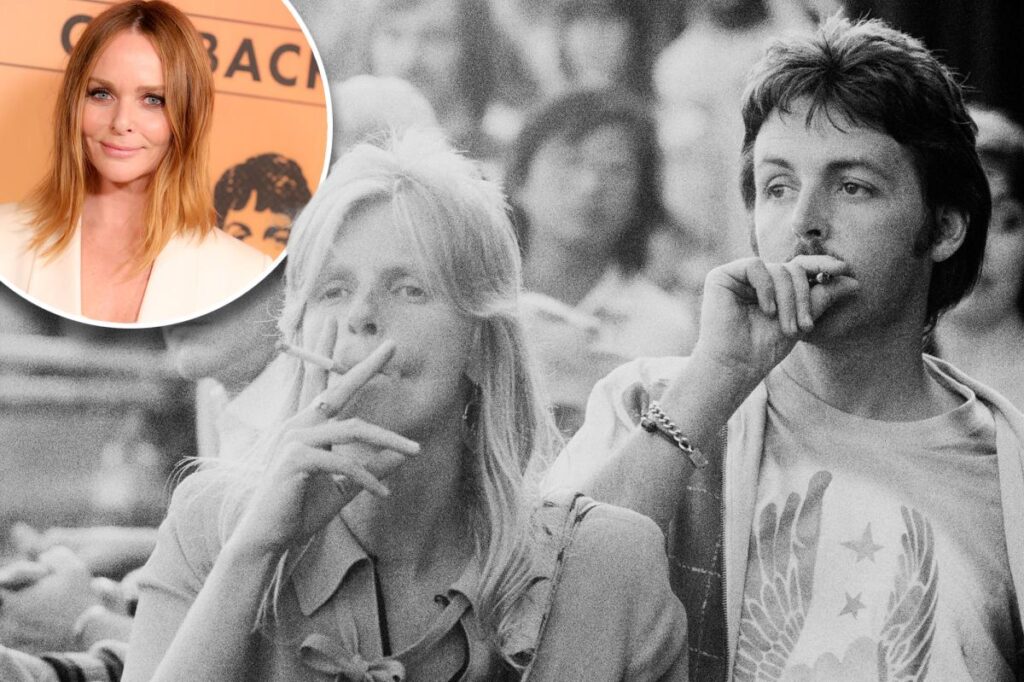

Stella McCartney was still a young girl when her father, Paul, was famously arrested in Japan in 1980 with nearly half a pound of marijuana. But she wasn’t surprised.

“I remember[the security guard]opening that suitcase, and I remember him picking up a pillowcase’s worth of skunk cabbage,” the fashion designer recalls in her father’s new oral history, Wings: The Story of a Band on the Run (Rivalite, out now). “Even a 9-year-old kid could hide the skunk cabbage better than my parents. But my parents said, “It would be a waste to leave it there.”

The book depicts the chaotic decade in which Paul struggled to figure out who he was beyond the Fab Four after the Beatles disbanded in 1970. Macca was frequently stoned and at one point was far enough away to see Bob Marley. He and his wife, Linda, formed Wings without even booking tour dates with the band and their children. Instead, one of the most famous musicians in the world showed up at the university and asked if he could play in his new band.

At the first gig in Nottingham in 1972, one attendee, Brian Pearson, recalled, “Linda was surrounded by an entourage of babies and young children, playing the keyboard and singing.”

At that point the band had 11 original songs in their approximately 33-minute set, and McCartney recalls refusing to play Beatles songs.

“They wanted it to be longer, so we repeated it,” he writes in the book edited by Ted Widmer.

Surprisingly, not every college they approached worked out, even for former Beatles.

“After Nottingham we decided to call Leeds first, but that wasn’t going to happen because they wanted a contract, proof of who we were, guarantees. So we did it!” McCartney recalls. “We headed straight for York. They didn’t have a big hall for us, so we rented a dining room.”

When he tried to play a show in Cardiff, he was turned away because the venue was being used for a badminton match.

In the city of Hull, McCartney fully realized how serious the trolls were.

The entourage, who were staying at what Linda called a “third-rate hotel,” were accosted by the night manager.

“This little bald guy came up to us and said, ‘Do any of you have that black and white dog?'” Wings drummer Denny Sewell recalls in the book.

“Paul says, ‘Oh, that’s my dog, Lucky. Why?’ (And the manager said), ‘Well, he was talking in the hall.’ We’ve got to clean this up.” ’ So Paul went and cleaned up. ”

Another big difference between being a Beatle and being part of Wings was critical reception.

Nineteen Seventy One’s RAM, the only album credited to Paul and Linda McCartney, was torn apart by critics.

Writing in Rolling Stone, Jon Landau called it “the lowest point in the deconstruction of 60s rock to date.” And Britain’s New Musical Express called it “an almost irredeemable journey into boredom” with “none of the music worthwhile or lasting.”

McCartney seemed to mostly ignore the pot, claiming that he had “learned not to care what they said,” but sometimes he just couldn’t ignore it.

He and Linda exacted terrible revenge after a British journalist wrote a terrible review of a Wings show he hadn’t actually seen.

“Stella was a baby at the time,” Saywell says in the book. “So Paul and Linda got a small plastic soap dish from the hotel we were staying in, took one of Stella’s feces, put it in the soap dish, wrapped it up and sent it to him.”

Paul’s ignominious arrest came at the start of Wings’ tour across Japan. Instead, the musicians got to see the inside of the cell block.

He spent nine days in a Tokyo prison. Until his last day, he faced the possibility of spending seven years there doing manual labor.

“It was the craziest thing in my life,” McCartney wrote.

Inside, the legendary Beatles were treated like any other prisoner.

“I woke up at 6 a.m. and had to roll up the thin mattress I had been sleeping on on the cold floor of my unheated cell,” McCartney wrote. “I had to wipe my cell with a wet cloth and wash myself with water from a cistern behind the flush toilet. Baths were allowed once a week.”

He had to share a bath with a convicted murderer while fully clothed for fear of sexual assault.

Other inmates tried to teach him some Japanese, but any attempts at communication ended in them gleefully shouting brand names at each other.

“I’d say, ‘Toyota!'” They’d say, “Toyota!” Toyota! And I heard them laughing,” McCartney wrote. “Then they say, ‘Rolls-Royce!'” I said, “Rolls-Royce!” You could hear them all applauding. I had to do something or I would go crazy. ”

Thanks to the efforts of Linda’s lawyer, her brother John Eastman, Paul was eventually released over a week later.

Apart from creative struggles and a stint in prison, Paul’s post-Beatles life also included difficult relationships with his former bandmates.

In February 1971, he had to sue them to dissolve the legal partnership.

“To this day, this is one of the hardest decisions I’ve ever had to make. Could I really sue the Beatles? They were my childhood friends,” he wrote.

After a lawsuit (a successful attempt to separate the band from its final manager, Allen Klein, who McCartney claims had inflated his fees), there was the question of how to reconcile with his estranged close friend John Lennon.

The two had been sniping at each other in public for years. McCartney finally lowered the temperature with 1971’s “Dear Friend,” a Wings song that includes the lyric “I’m in love with a friend.”

They met again in New York at the end of 1971. Their awkwardness quickly resolved, and the two songwriters remembered why they were so close.

“Once we talked, the atmosphere got better and it was great,” McCartney remembers.

John and Yoko gave him a bootleg record of the Beatles’ original 1962 Decca Auditions. British labels had infamously discontinued the band.

“It was one of those moments where we remembered why we were such great friends in the first place,” he recalls. “[John]wrote on it, ‘They were a good group. It would be a waste to turn them down!'”