Juliet Binoce won an Oscar for “an English patient.” From Leos Carax to Abbas Chiarostami and Olivier Assay, we have worked with the great Autel. And among her many achievements, she took the lead side of the Juice of Cannes and Berlin. However, in the classic Juliet Binoche style, the iconic French actor did not take an easy route to direct her first film.

Today, “In-I in Motion,” which premieres worlds at the San Sebastian Film Festival, portrays her chaotic, dazzling, and ultimately cathartic experiences, making it difficult to create a sabatic year and half of the clergy in 2007. Binoche talks about diversity ahead of San Sebastian. This is because it requires transforming 170 hours of footage, chasing the musical rights of songs used during countless rehearsal sessions, and editing abstract material into films. The result is an equally intellectual, political and visceral work that reflects the nature of artistic creation and emphasizes Binoce’s character and preference for the challenges that deprive the boundaries.

On paper, the story of a famous actress who learns how to dance with a famous choreographer may sound like a romantic comedy pitch, but “In-I in Motion” depicts the physical and emotional challenges that not only reveal her fears and restore some trauma, but also allows her to run around the world. In addition to director, Binoche also produced the film alongside Miao Productions’ Sébastien de Fonseca. In the interview, Binoce also talks about how Robert Redford gave her the urge to film her performances, discussing the political aspects of “in-i in motion” and the artist’s role in society.

First, I wanted to say that just watching you dance on “In-I in Motion” made me miss breath. It’s impressive!

Ha, I was breathless too!

Even if you weren’t a professional dancer, why did you want to create this show by incorporating sabbaticals from your busy acting career?

I sometimes take breaks, one of them used to co-create this show with Akram Khan for about a year and a half or almost two years. I think it’s important to apply these brackets to nourish yourself or to reintegrate your desires in some way. I love diving into other worlds.

Where did the idea for this collaboration with Akram Khan come from? Did you know him?

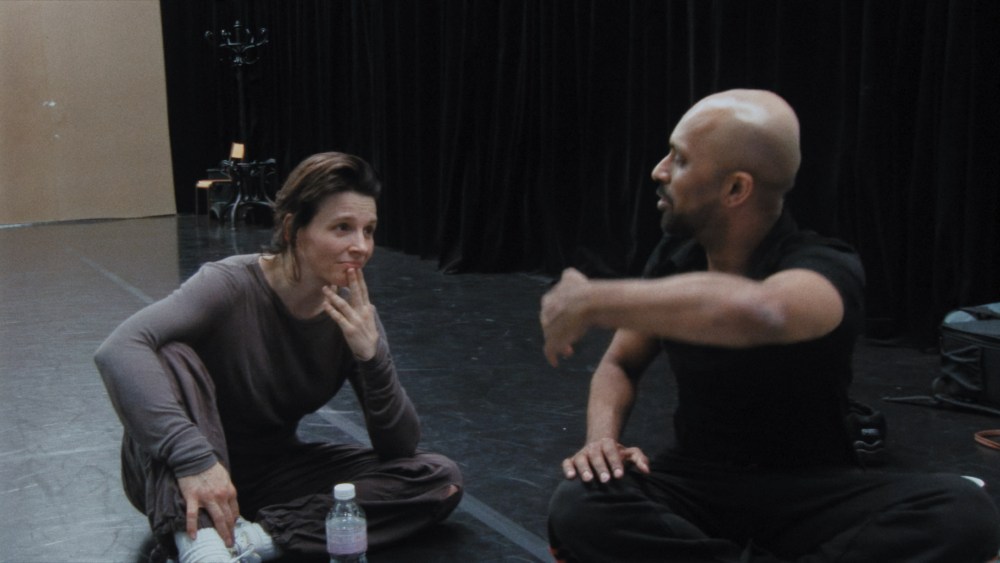

In fact, it started when I was being massaged by Su-Man HSU, which you can see in the film, as I was the rehearsal director. She does many different things, one of which is directional massage. So I was filming in London and she was massaging me, which was very painful. And when she planted an elbow on my back she said, “Do you want to dance?” And I said, “Yes.” And she invited me to see Akram Khan’s show while her husband, Farooq Chaudhry, was producing. So I watched the show and discovered it was seductive. And finally, they let me meet Akram and they said, “Do you want to improvise for a few days, see if you can do anything together?” And we did it. And then we said, “We enjoy each other’s company. It was a good experience.” So we said, “Okay, we’ll see each other in two years.” Because he was on tour and I was filming. And finally we entered each other’s world. And while it was appealing, it was very difficult, at the same time, as it was difficult to get into other people’s crafts. It takes courage. There are moments when you are completely lost and your body is not ready to go. For Akram, it was more emotional, he wasn’t ready to go there. So it’s like being on the edge of a cliff and seeing a huge blank in front of you and behind you. And you just had to jump and do it regularly.

And it worked well since you toured “In-i in Motion” in 100 cities! At what point did you decide to film the show?

Yes, we were on tour and we went to many different continents for months. After that we arrived in New York City and danced at the Bum Theater. And then Robin Redford came to my dressing room and he said to me, “You have to film this film.” And he was so intense and passionate about it, so I said, “Yes, I was thinking about it.”

But we only toured for another month. “How do you handle this? You have to make it happen!” And I didn’t know how to handle it and if I could one day put it together. And then I found out my sister had come to the rehearsal room and I asked her if she could shoot seven shows at different angles, and she did!

How did you fund this directorial debut?

I had Ora Strom, a Norwegian investor. He came with his partner Soren Leger. And I said, “Well, I have this thing in my drawer, and I dream of one day taking the time to do it.” And since our meeting at Cannes, it took two years, as digitalizing tapes has already been a big thing. And when we were rehearsing, we put some different music to see where it took us, and also got the rights to those songs. There was also a 170-hour video!

Did you want to give up on this movie at one point?

Well, sometimes I was very pleased with something, and at other moments I felt like, “This is bullshit. This won’t go anywhere,” so I was desperate. There were bad days and good days. So it took a while. I started working with one editor, and the second editor came afterwards. And the last editor assistant helped me. Because I was still working on it first. The first cut was nine hours. And then I said, “Okay, how do you deal with this?” I had to cut back on the photos for each scene. I was able to visualize the film, so it helped me. Previously, it was abstract and visualization of the scene was really key to me.

How transformative was the experience of creating this dance performance in your life and career?

I don’t think I was too scared of taking risks after this experience. It really brought me to the edge of fear. Every night, this show was so tough, physically and emotionally, I thought I would never survive this show. It was both. Usually, as an actor, you can do physical things at times, but the combination of both is very rare. And in this show we created, it was both. And I really felt I had no intention of surviving. That was the feeling every night.

You will not only co-create the choreography, but you will also write most of the politically charged dialogue/monologues.

Well, I don’t think it was streamlined. I think it came from my life at the time, and probably a while back in my time. As a young girl, I fell in love with a man while watching “Casanova.” He was the man sitting in front of me and I couldn’t even see. But then he took me on a journey to have him. And we began a story like this. It’s an interesting theme to know that we were in the world of #MeToo now and that it was actually the young girl who started this need for love. And from that point on, we developed the story. Then my character on the show breaks when she is attacked by a man who wants to strangle her. It happened in my life too. So we were experiencing some very personal subjects that are being talked about now.

Akram Khan likewise talks about his own trauma in “In-I in Motion.”

Yes, he also talks about the deep betrayal he felt as a young boy, so we know that his father had witnessed all this and probably arranged it. His father was still alive at the time and probably didn’t want to expose him, so he didn’t want to keep it on the show. But even so, it shows a little boy in a Muslim setting, and someone who is betrayed and treated horribly. It all came together when we were doing it. I don’t think Akram wanted to do a show about the relationship. I don’t think that was really his purpose. But at that moment I saw me with the need to understand what my life was and accepted it to him.

Do you want to direct other films as you enjoy taking part in the creative process?

of course. At the same time, I can’t plan my life. Life is even more mysterious than that. And I love the fact that I was able to find the last two years in my life. And I did the plays and films and I was able to focus on it. I felt it was authentic. But at the same time as the actor, you are in the midst of creation and, in a way, co-create.

But as an actor, you rely on the desires of filmmakers. You don’t have that much control, do you?

I’ve heard directors who hate shooting times because they really are 50/50 when we’re on set and actually embody what the actors wrote. Then there’s another story in the editorial office. But if the actor is not happy with the editing, he might say, “I’ll fuck you. I won’t go around the world and get promoted.” Do you understand what I’m saying? So it’s definitely codependent.

You served the ju umpire in Berlin a few years ago and gave Israeli filmmaker Nadab Rapid the “synonym” Golden Bear. He is now worried about the pressure from the Israeli government on artists who are becoming increasingly isolated.

It is in the history of the film when we saw Eisenstein, who was unable to finish his final film because it was in Stalin’s hands. And that’s part of being an artist and being resistant. And when you have resistance, it means society is healthy. That means not everyone thinks the same. Not everyone is under the same rules. You need to be independent in your feelings and ways of thinking. And that’s that they integrate each other. I think it’s a very necessary action to think about it in order to question the current situation. The artists are not established, but they are there to become who they are.

Nadav Lapid, like other Israeli artists, is worried about a boycott call and the possibility of entering the festival again.

Nadav is a very powerful artist. I don’t think he should be too worried. He is a great director, he has his own perspective, and we need it too. But I don’t think he’ll be rejected. I think there was a problem with Cannes, but I really didn’t get into it because it wasn’t my place. And of course, he was frustrated that he didn’t participate in the competition. But you also have to be patient when you are a director. You really need to go for your path and what you feel, what you think, and for it. And he might do a cheaper little movie, who knows? But he has that talent. He is very wonderful. I am captivated by his talent. He asked me to write a bit of a preface for his book this summer, so I watched all of his films and I can make sure he is extremely talented.

And this year, your Cannes ju umpire gave finalist Jafal Panahhi the Palme Door to represent France at the Oscars (interviews were conducted before Panahahi was selected as an official French submission)?

That’s great. It should be on the Iranian list, but if it’s a French list, get it.

Unfortunately, it cannot be listed in Iran.

Probably one day!