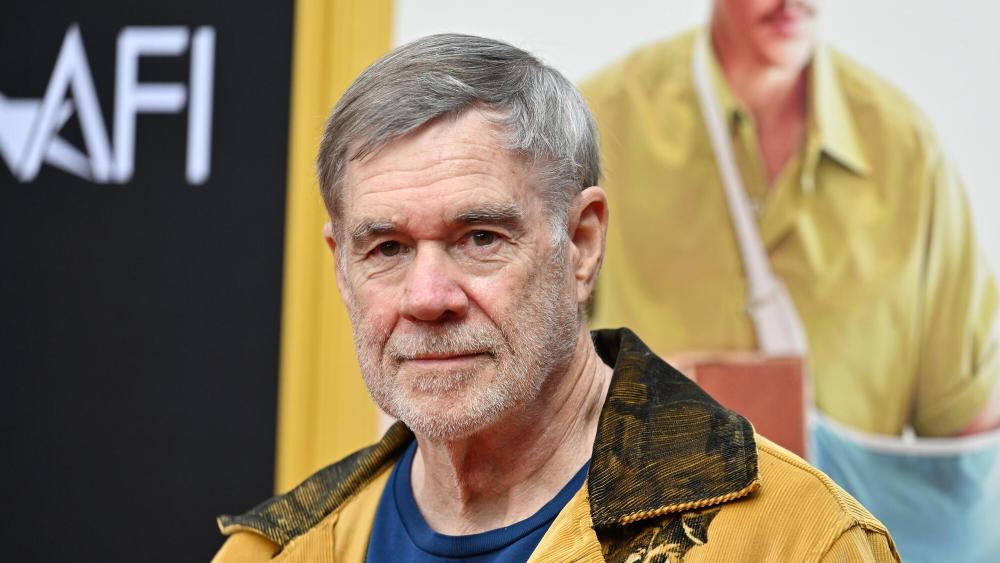

Gus Van Sant is still on the move.

“I think a lot of the movies I’ve made are based on real life, even if it’s unintentional,” Van Sant says in his usual mixture of understatement and curiosity. “I think it’s kind of a genre. I’ve always been drawn to things that make people take action.”

Van Sant’s latest film, Dead Man’s Wire, which premiered at the AFI Film Festival on Saturday, is literally electric. This historical crime drama, based on the 1977 Tony Chiritsi hostage crisis, unfolds like a pressure cooker between despair and spectacle.

“When I read the script, there was a link embedded. When I clicked on it, I heard the actual 911 call. Tony spoke fast like Scorsese the cocaine vendor, cracking jokes and throwing tantrums. I thought, ‘This is a great character.'”

There’s a quiet thrill to Van Sant’s words, echoing a writer who has spent his career balancing empathy and danger. From “Drugstore Cowboy” and “My Own Private Idaho” to Oscar-nominated “Good Will Hunting” and “Milk,” he has never pursued a single genre. Only human actions.

“There was a weird barnstormer-like energy to this story,” he says. “We were having a meeting at Soho House, and the producer said, ‘We have to start shooting in Louisville in two months.’ That was the most appealing thing. We just hit the road like Huckleberry Finn.”

Van Sant, now 73, feels nostalgic when he talks about creative chaos. “The best part of the movie is definitely the accident,” he says. “River Phoenix loved having the unexpected happen on set. He was so alive in the moment that he could feel his character reacting in real time.”

While “Good Will Hunting” (1997) lost most of the awards to “Titanic,” its memory lingers, as does one of the fog machines that made him sick at the 1998 Oscars.

“I’m allergic to stage fog now,” he says with a laugh. “That’s why I never use it on set.”

Seven years after his last theatrical film (Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot), Van Sant is back with a story that reflects his fascination with the tragedy and absurdity of America’s real life. The director remains fascinated by the fine line between empathy and obsession.

With “Dead Man’s Wire,” Van Sant has delivered his most shocking and provocative work since “Milk.” The film shows a honed maturity in tone and control, singing with the restless energy that characterized his masterpieces such as the early 1970s. Skarsgård gives a career-best performance, anchoring Tony Kiritsis’ volatile character with flashes of humor and heartbreak, while Dacre Montgomery and Coleman Domingo deliver richly textured performances. Oscar dark horse? of course. But that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be considered. Van Sant’s direction, in particular, is at once intimate and explosive, constructing chaos with empathy and making the audience feel the pulse of desperation behind every decision. The film’s script, adapted from true events by first-time screenwriter Austin Kolodny, is infused with humanism and dark wit, making it one of the best scripts of the year.

In a wide-ranging interview with Variety, Van Sant talks about his past, present, and future in the industry he’s spent more than 40 years mastering.

“Dead Man’s Wire”

Stefania Rosini SMPSP

Looking at your filmography, this matches your interest in real people and crime.

Yes, I think so. Many of my films, even fiction, are based on something in the real world, such as a news story or article. “Drugstore Cowboy,” “Elephant” and “Last Days” were all born from that impulse. It’s not “true crime” like on TV, but about what drives someone to act in a certain way, the questions that lie inside the crime.

How did you choose Bill Skarsgard to play Tony and Dacre Montgomery to play Richard?

Casting was probably as important as the script. One weekend I was at a spa, listening to some ambient music, trying to decide if I should jump into this project. Filming was to begin in November. I’ve always wanted to work with Bill. I had offered him the role before that didn’t happen. He’s had a fascinating career in horror films, but he’s like Lon Chaney, the man with a thousand faces. That was interesting because he’s 10 years younger than the real Tony.

I learned about Dacre through her audition tape for “Stranger Things.” This is one of those legendary tapes that actors circulate: perfect lighting, perfect eyeliner. At first I didn’t even watch the show, I just watched his scenes. He felt new and unpredictable, and that’s what the movie needed.

And Colman Domingo as a radio DJ – that’s a very inspired choice.

In fact, we modeled the character after DJ from Warriors. It was in the script. We had several actors pass on it before Coleman came along. He was working on another project with producer Cassian Elwes and said, “I’d love to work with Gus.” He was perfect – his presence grounded the movie.

Fans always ask if I would like to see “Drugstore Cowboy” again.

In fact, there’s a script written by the same writer, James Fogle. There were four different ones, one of which was called “Satan’s Sandbox,” which I think James Franco wanted to do, but I preferred that one. The setting is San Quentin Prison. And actually, when we met him and made this film, he was in the Walla Walla State Penitentiary in Washington state, so when he got out of prison, he had some stories about when he was running around selling drugs and stealing drugs, like “Drugstore Cowboy.” There are others, yes, there are others.

River Phoenix was a huge influence on your film journey. He’s definitely one of the core reasons I got into movies myself. How often does his mind cross your mind?

I mean, I think about him all the time – I have a picture of him on my wall. He was, so to speak, a great collaborator. And we only made that one piece, and we were planning – he was planning to become “Milk” later on. But it happened much later, before he passed away, so there was a project that we were talking about. But yeah, he was very spontaneous. He loved to improvise. That was his favorite thing. And I don’t think I necessarily had to improvise off the page, depending on who I was working with. It probably wasn’t the type of movie he was doing. He was doing the kind of traditional work that would be done safely in Hollywood. He was doing traditional pieces and that was what was offered to him.

And in that environment, you don’t make movies where you improvise entire scenes, as you’re referring to Scorsese. And when we did that, he realized that I liked it, I mean, I was fine with just doing something that wasn’t even in the script for like five minutes. Because that way he can really look into things and feel very open about what he’s playing. It was kind of magical and he liked it, but he couldn’t do it. He was so excited because he doesn’t usually do that.

I don’t know, there are many things. Because of the way he was brought up, he didn’t have a lot of film history associated with his memory bank. He did not have much knowledge of the war, as he was educated at home. His homeschooling was without war. Therefore, people like General MacArthur did not exist in his world and he did not know who they were. And on the contrary, he did not know what humor was. He didn’t know what a quote and unquote joke was until he was 9 years old, he said.

He realized this because he went to a traditional school, a public school, and the kids were making jokes. A time when kids were into jokes. he didn’t know what it was. They seemed completely foreign to him. He didn’t have a smile either, which people don’t necessarily know. He said that to me – “Well, I don’t have a smile.” And I said, “You’re kidding.” Then he smiled and gave me a smile, and I said, “Oh yeah, I don’t see that smile in your movie.”

I mean, he had something interesting. For a movie star, such a huge smile was curiously lacking. But on the other hand, he was very funny and loved nothing more than to just laugh and tell stories.

You’ve been nominated for an Oscar twice. What do you remember about that morning?

Most of the time, I had no idea when the announcement was being made. I woke up to a lot of phone calls. It’s a big Hollywood award – it’s a great feeling. At the “Good Will Hunting” ceremony, this giant Titanic ship set was unveiled and fog filled the area. I felt so sick sitting there that I swore I would never use fog on set again.

There is a lot of talk about the “death” of movies. do you believe it?

Not at all. Movies are always following technology, from Nickelodeons to iPhones. What matters is coming together and that communal experience. The art form is not dead. It’s just changing. The best movies of the 1920s were miracles. Because no one knew what movies were yet. We are once again in a period of discovery.

Can we expect another movie soon or will we have to wait another seven years?

i hope so. I did the Gucci project and the six-hour “Feud,” so I wasn’t slacking off. I have hundreds of ideas and digital files full of them. Some products, like milk, may take decades to develop. But they’re there, waiting.