After screening THX 1138 at the Cannes Film Festival in 1971, director George Lucas was reportedly in desperate need of money to pay for a hotel bill.

There he met with David Picker, then head of film studio United Artists (UA), who tried to get him involved in several projects.

“We’ve got something that’s like a space opera. It’s like an action-adventure movie in space,” Lucas said, pausing.

By the end of the conversation, the then 27-year-old Lucas had signed a deal giving up the rights to Star Wars and American Graffiti for a total of just $10,000.

Fortunately for Lucas, the script for “Graffiti” was unsatisfactory, and UA ended up canceling both projects. Years later, Picker confessed that he didn’t even remember making the trade, given how small the amount was.

This anecdote is one of many in Paul Fisher’s new book, The Last Kings of Hollywood: Coppola, Lucas, Spielberg, and the Battle for the Soul of American Cinema (Celadon Books, on sale tomorrow), which charts the winding and bumpy roads these young directors took to make some of the most iconic films in history. They were certainly creative geniuses, but they also had plenty of bad ideas and moments of poor judgment.

When the three directors first met for lunch in 1969, Spielberg, then 22, told them about a film he hoped Universal would greenlight to direct.

“It was a sex comedy, a retelling of ‘Snow White,’ replacing the dwarfs with seven men running a Chinese food factory,” Fisher writes.

Thankfully, Universal rejected the idea a few weeks later.

At that point, Lucas’ American Graffiti had been accepted to Cannes, and Lucas was offered to direct both the film version of The Who’s rock opera Tommy and the rock musical Hair. Despite being extremely poor at the time, he rejected both, insisting instead on creating his own original work.

Meanwhile, Spielberg was hired to direct “Jaws” after the studio’s first choice, TV commercial director Dick Richards, met with studio executives and kept referring to the shark in the film as a whale.

Lucas, along with Scorsese and screenwriter John Milius, stopped by Spielberg to see the film’s mechanical shark structure, which resulted in the director pulling a bigger prank on his friend than expected.

“George stuck his head in[the shark’s]mouth to see its inner workings,” Fisher wrote. “Stephen jokingly pulled the lever that closed the shark’s mouth, trapping George inside. Stephen, Marty, and Milius pulled and pulled, forcing the jaws apart, and after several minutes of sweaty, panicked struggle, they managed to free George.”

That was just the beginning of an eventful filmmaking process.

Only a week before filming was scheduled to begin, director Spielberg had not yet cast one of the lead roles (police chief Brody, shark hunter Quint, and oceanographer Hooper).

“Stephen’s first choice for the role of Quint, Lee Marvin, turned him down,” Fisher wrote. “Jon Voight, Timothy Bottoms and Jeff Bridges left Hooper dead.”

Charlton Heston wanted to play Brody, but Spielberg thought he would “be in the movie and overwhelm the balance of the cast.”

A few days before filming began, Spielberg ran into Roy Scheider, who had just been nominated for an Oscar for his role in The French Connection, at a party. Within minutes, he had Brody.

Lucas recommended Richard Dreyfuss, who starred in American Graffiti, for the role of Hooper, but Dreyfuss passed on the role because he disliked the script. Only after meeting with director Spielberg and refining the script did he agree to accept the role. Robert Shaw was soon cast as Quint.

And the residents of Martha’s Vineyard thought the film crew were idiots.

The camera team was unaware of the ever-changing light in the vineyard and was constantly changing the lighting.

“‘Don’t you see,’ said those who were there, murmuring to one another, ‘the water is different, the light is different?’

Residents also watched on in disbelief at the fake shark. “No one bothered to ask local fishermen about alternatives, otherwise they would have been told that dozens of tiger sharks could be caught just a few miles away at any given time.”

The movie’s most famous line, “We’re going to need a bigger boat,” was an actual line of criticism repeated by residents whenever something seemed amiss during filming on the water. This line appeared in the film because Scheider kept inserting it in defiance of Spielberg’s rage each time.

Spielberg initially disliked John Williams’ iconic two-note musical theme. When the director heard the song for the first time, he laughed in the composer’s face and said, “You’re not serious.”

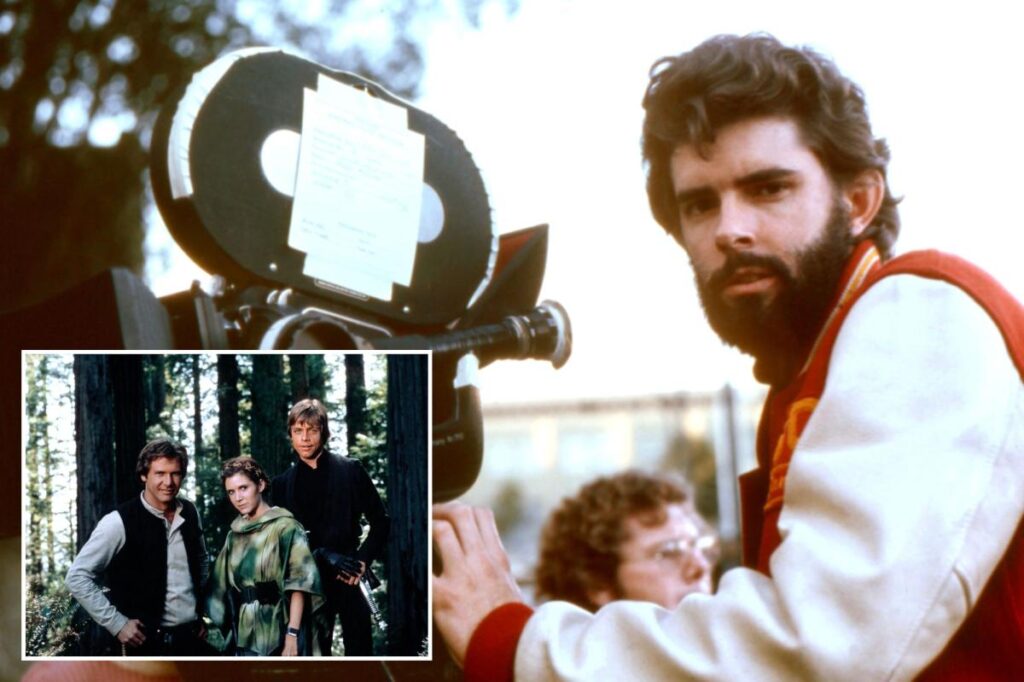

Meanwhile, Lucas was trying to sell “Star Wars.”

He showed the script to his friend William Friedkin, director of The Exorcist, and he said, “What is this?”

Lucas eventually signed a deal with 20th Century Fox, but said that Alan Ladd Jr., then the studio’s vice president, didn’t really understand the film.

“I don’t understand this at all, but I think you have talent and I hope you succeed,” Rudd said.

Casting director Fred Roos was convinced that Harrison Ford should play Han Solo, but Lucas wanted someone unknown, someone he had never worked with before, and Ford had appeared in a bit role in American Graffiti.

But Ruth was so convinced that she arranged for Ford to attend Lucas’s meetings, disguised as a carpenter by trade.

Lucas walked in and saw Ford on his knees working on something with his tool belt. It looked “no different than a gun belt.” The director encouraged him to read for the role.

Meanwhile, the studio wanted Al Pacino to play Hans Solo, but later passed on the role, saying he “didn’t understand the script.”

The casting session was a rare double act, as Lucas shared the casting session with Brian De Palma, who was in charge of casting Stephen King’s Carrie. Actors performed reading roles in both films.

Over the course of three days, the two met with “all the up-and-coming actors in Los Angeles.” Those who didn’t get roles in either film were Kurt Russell, Christopher Walken, Farrah Fawcett, Sigourney Weaver, and Karen Allen, who would later be cast by Lucas and Spielberg in the Indiana Jones series.

Initially, the character of Princess Leia was seen as a young teenager. Director Lucas wanted to hire 13-year-old Jodie Foster, who had just finished filming Taxi Driver, but she had already signed on to appear in Disney’s Freaky Friday.

Lucas also strongly considered 14-year-old Terry Nunn, who would rise to fame in the ’80s as the singer of the band Berlin.

He ultimately aged up the character and cast Carrie Fisher.

The shooting itself was a huge failure.

“None of the special effects worked out as well as[Lucas]had hoped,” Fisher wrote. “The awe-inspiring world he invented looked like cheap rubber and plastic.”

The cast teased him mercilessly.

“Hamill joked about George’s instructions and apparently all he said was, ‘Faster!’ or ‘Harder!’ and Ford routinely poked fun at the script,” Fisher writes.

When filming on the film finished in July 1976, Lucas was “very depressed about the whole filming experience.”

However, director Spielberg thought the Star Wars set stills were so good that he suggested trading one profit point from Star Wars for a profit point from Close Encounters, which he was filming at the time. Lucas, who thought Star Wars points were worthless, agreed.

The director and friend would later team up on Lucas’ idea for an adventurous archaeologist named Indiana Jones. Paramount refused to hire Spielberg to direct “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” citing Lucas’ failure with the over-budget comedy “1941.” Lucas won this battle only by promising, along with Spielberg, to cover all costs and budget overruns himself.

As with any film, the initial vision did not always match the final cast. Both Lucas and Spielberg wanted Tom Selleck to play Indiana Jones, but he had starred in Magnum P.I.

By the end of the 1970s, Lucas and Spielberg had conquered Hollywood, making four of the top 20 highest-grossing films of all time. “Star Wars” came in first place, “Jaws” came in second place, and “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” came in 7th place. “American Graffiti” ranked 13th.

Spielberg, who was recently named an EGOT, went on to a prolific and legendary career, but Lucas didn’t direct again for more than 20 years until the release of the Star Wars prequels in the late ’90s. He sold Lucasfilm to Disney in 2012, including full rights to the Star Wars and Indiana Jones series, for more than $4 billion.

Fortunately, David Picker had a terrible memory.