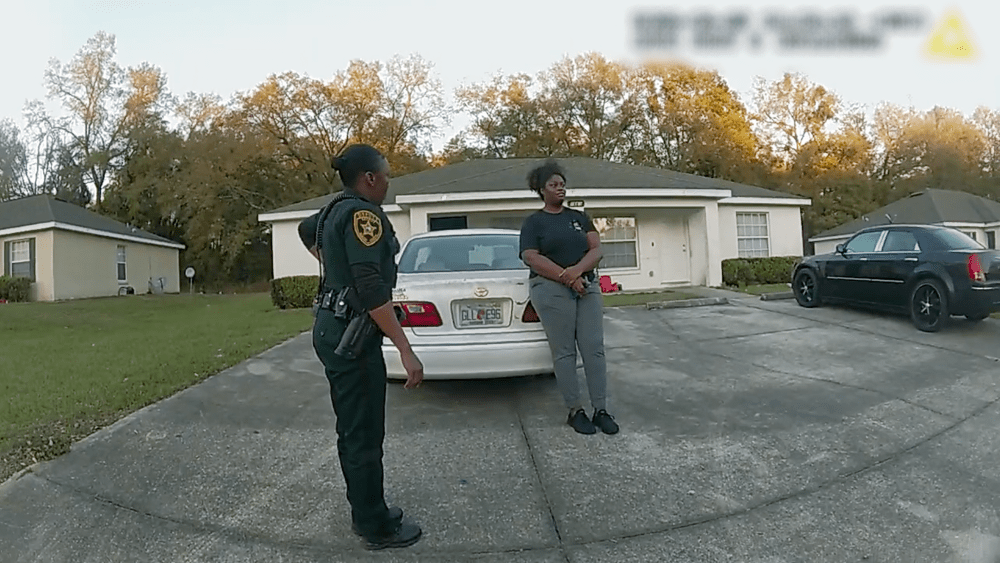

In Perfect Neighbor, director Gita Gundbir relies on police body cameras, ring cameras, cell phone footage, and recorded 911 calls to tell the story of a small Florida neighborhood dispute that escalates into deadly gun violence when Ajike Owens, a young black mother of four, is shot and killed by her white neighbor Susan Lorinx.

The doc, which won the Jury Prize at Sundance this year and was acquired by Netflix for a reported $5 million, is currently streaming on Netflix and is part of a growing number of nonfiction films that utilize body camera footage. Last year’s Oscar-nominated short documentary “The Incident,” produced by The New Yorker, relied entirely on body cameras and surveillance footage, and this year’s “2000 Meters to Andriivka,” about the Russia-Ukraine war, incorporated body camera footage from the Ukrainian military.

“I feel like this is not just a trend in the documentary world, but a global trend,” Gundbiel says. “We now live in a world where media production is in anyone’s hands.”

For “Perfect Neighbor,” Ms. Gundbiel decided not to use Talking Heads, recreation, or traditional documentary storytelling techniques for several reasons. The first is that we don’t want to “re-traumatize” Owen’s family and community.

“We had all the material, so why would we let them talk about what happened and relive it?” Gundbiel said. “Body camera footage is undeniable. It’s institutional footage, but it’s not biased by us as filmmakers, journalists, on-the-ground reporters. I don’t think it’s possible to deny that this is a sequence of events that occurred for viewers who now frequently question veracity, credibility, and perspective.”

The director also wanted to “flip the body camera footage.”

“Police body camera footage is typically used for community surveillance,” Gundbir said. “This is used to protect police. For people of color and vulnerable communities, it’s used to criminalize us. To dehumanize us. It’s a tool of surveillance, and I wanted to flip it and destroy it to make this beautiful community look like it was before. Just like you actually use footage to humanize people in that community, and we don’t have to do things like that.”

Gundbiel worked with editor Viridiana Lieberman to condense 30 hours of footage into a 97-minute documentary.

“We chose when to let things unfold and when to accelerate it,” Gundbiel adds. “The idea is that there’s an idyllic small town, and there’s an immediate threat that only the children are aware of. The adults, including the police, see Susan as nothing more than a nuisance.”

In the documents, an adult neighbor told police, “That woman (Lorinz) is always messing with other people’s children.” She pointed to a vacant lot where black and white children liked to ride their horses. “She’s bossy,” the girl said, recognizing Lorincz as an angry “Karen.”

In the lead-up to the 2023 shooting, Lorintz consistently called 911 over a two-year period complaining that Owens’ children and other neighborhood children were making too much noise and playing on “her property.” Police first responded in February 2022 and came out to interview neighbors after Lorincz accused Owens of throwing a “no trespassing” sign. A steady stream of police visits to Florida neighborhoods followed.

Gundbir describes the film’s pace as a “slow burn”.

“You’re having these revelations that make you deeply uncomfortable all the time,” she says. “This is a horror movie in many ways.”

Lieberman intentionally delayed the climax of the film’s gruesome filming, which was not caught on camera. The editors used audio recordings from doorbell cameras and a series of 911 calls to give viewers a sense of the conflict that was very different from the life-or-death scenario Lorinci describes to the police officer.

“There were certainly a lot of steps that needed to be unpacked to fully experience that night,” Lieberman says. “The emotional outburst and turmoil of the actual event itself came from so many different angles. So I would say cutting it out and choosing who to be with, where to be, and when was the most difficult part of making this film. The first cut that night was 40 minutes.”

Many critics have called Perfect Neighbor a true crime documentary, a label that makes Gambhir “offensive.”

“A lot of times when people think of true crime, they think of something sordid or procedural,” the director says. “This film is definitely about crime, but I never thought we’d set out to make something like an actual crime documentary film.”

It may not be your typical full-on crime doc, but like many films in the genre, Perfect Neighbor does include some trial scenes, but few made it to the final cut.

Lorincz, who invoked Florida’s stand-your-ground law, went to trial last year. Mr. Gundbiel and Mr. Lieberman had already completed the final cut of “Perfect Neighbor” for Sundance, but after seeing the trial, which ended in November 2024, they decided to incorporate it into the doc.

“We talked a lot,” Gundbiel said. “The trial was fascinating, so we thought we should weave it in, and all of a sudden you could see all the people that were on the body camera footage. It was like the cast suddenly appeared and you could see everyone in clear light.”

Ultimately, Lieberman reduced the four-day trial to a two-minute sequence, which ran during the Doctor’s credits.

“Nobody can fast forward the credits these days,” Gundbiel quips.