The fence in the title is not awfully impressive. Utilitarian and standard wire boundaries, no protection from bent or broken or outer eyes. But it is the symbol of many of Claire Dennis’ stripped, candid new films, between the two men on both sides and the barrier that has not been proven to be as fixed and difficult as the tense society. There are outsiders inside. White Western intruders become those who stepped into and built “Western African construction sites,” as the opening title card simply declares. A “fence” is simple. This is an unusually sharp, surveillanced rhetorical work from this typical oval and sensual filmmaker, but the rage that swells beneath its stationary surface is not.

“Fence” represents the director’s departure in a way. It’s her first stage adaptation, one thing, and makes little attempts to hide their roots. For the first time since the Immaculate Continent, Dennis has returned to the continent that shaped her childhood – the daughter of a French civil servant is stationed on multiple West African territories – and weaved from the nostalgia of barbed wire colonialism through the “Biu Travile” of “Chocola” through her first feature, “Chocolat.” She also returns to Ivolian actor Isahachi des Bankre, who has been a recurring presence since her debut.

We are in the same modern, unidentified postcolonial terrain as the “white material”, which was flatter and thirsty, but we are welcomed by the white settlers and developers that did not actually expand in the first place. The fence is standing for now, but its long, frictional retention patterns have broken into something more violent. It surrounds private construction sites with unclear purpose besides lining up Western pockets.

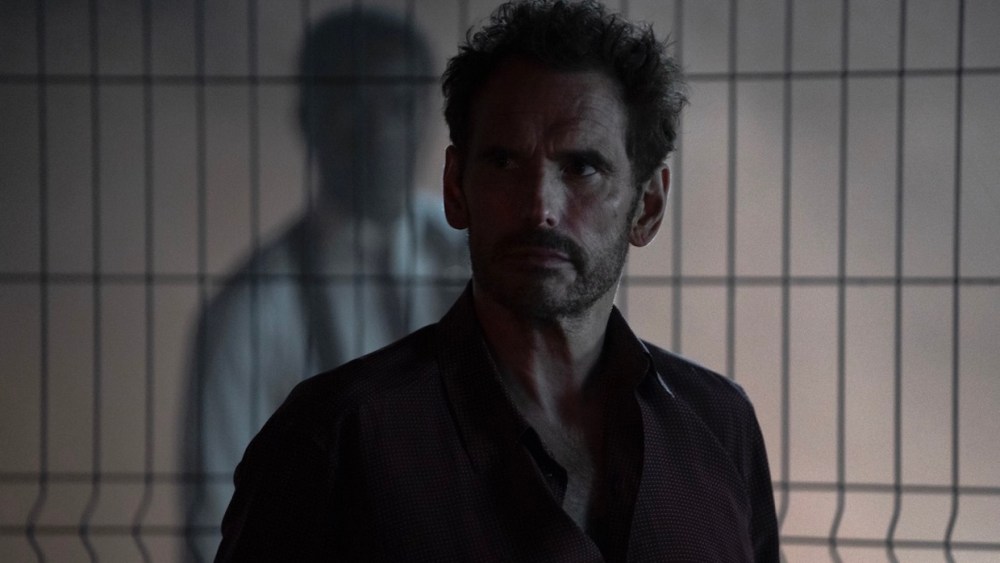

At the beginning of the closely trapped story, which lasts less than 24 hours, one of these workers has just been killed, claiming that Horn is an accident in an unfortunate place. That night, the dead man’s brother, Albauri (de Bankolé), appears and gathers his body and takes it home. Allowing Horn to doubtfully dislike him is a simple request, instead glibly invites Albery into the compound for a reconciliatory drink. He is politely but firmly rejected by the visitors – calmly dressed a bit surreal in the favorable, pristine chark stripe suit of producer partner St. Laurent. One person is not physically moved, the other person is not emotionally moved. DeBankolé’s soft, stoic calm and Dillon’s grumpy, spiral frustrators are equally at odds.

It is a fierce position filled with implicit accusations and hostilities, and could exist all tacitly for many racial injustice and inequality that still linger after the era of colonial occupation. Dennis’ script, co-written with Andrew Litbach and Suzanne Lyndon, is adapted from “The Black Battle with the Dog,” a 1979 play by Frenchman Bernard Marie Cortez, and despite the existence of smartphones (intervention by the lack of signals), the film is here in any way, halfway through the last half century, and halfway through the last half century. The spirit of Western qualifications. (Cal is sung to “Beds-Addise,” the national anthem of Indigenous land rights by Australian Rockers Midnight Oil.

The mutually meaningless conversation between the two men presented as measured dimly shot reverse shot volleys by Dennis, DP Eric Gautier and editor Guy Lecone is also a blatantly rooted, yet oddly persuasive, psychological reign. Dennis doesn’t appear to be entirely home with such rigid oral substances, and performance is sometimes dictated with uncertainty. Dillon is a proper foreign presence in this serious environment, but sometimes the horn appears to be more clearly present than expected.

However, the volatile dynamism at the film counter comes from the rise of Brittstar Bryce and Mia McKenna Bruce. Fresh from the plane from London with hopeless strappy heels, and not ready to the implicit battlefield she stumbles, she is quickly set to combat mode in a fierce cal in the boolean when she picks up her from the local airfield and becomes immediately hostile.

But we also feel the test-like desire there, recharge and complicate other tough setups, combining them with what could be a strange signal elsewhere to be. Suddenly, we are in the more familiar terrain of Febril Dennis. The expected Uzi scores by her longtime collaborators may kick at a very late period in these quiet and echoing proceedings, but other filmmakers have not been able to squeeze the film-like sweat from Kylie Minogue’s drone nu-disco.

Both old and a little newer from her, “fence” is not the main Dennis job. That gear changes from the arch, and from the theatrical parable it is not smooth to a supple mood piece. But it steadyly shakes you, like that Kylie Earworm. “It’s very unrealistic here,” says Leonie. In just a few hours to her African Odyssey, her gaze still flts the fears and fantasies of outsiders. “It’s very real, you’ll see,” Cal corrects her. “Fences” can be distracted by a sensual world with an obstructive perspective in mind, but most are trying to dull all the heat and dust.